Towards Interpretable Protein Structure Prediction with Sparse Autoencoders

Authors

Abstract

1. Introduction

Protein structure prediction has seen revolutionary advances with the introduction of large language models like ESMFold [1] and AlphaFold [2]. These models can predict 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences with remarkable accuracy, often rivaling experimental methods. However, there's a significant drawback: we don't fully understand how these models translate sequence information into structural predictions.

This interpretability gap isn't just an academic concern. Better understanding of how these models work could enable more targeted protein design, provide insights into protein evolution, and potentially uncover new biological principles. But the nonlinear, high-dimensional nature of these models makes them difficult to interpret [8].

In this work, we make two key advances to address this challenge:

- Scaling sparse autoencoders to ESM2-3B, the base model for ESMFold, enabling mechanistic interpretability of protein structure prediction for the first time

- Adapting Matryoshka SAEs for protein language models, which learn hierarchically organized features through nested feature groups

2. Methods

2.1 Problem Setup and Models

Our goal is to develop interpretable representations of protein language models that can explain how sequence information is translated into structural predictions. We approach this by training sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on the hidden layer activations of ESM2, focusing on the large 3 billion parameter model (ESM2-3B) that powers ESMFold's structure predictions.

Formally, given token embeddings from a transformer-based protein language model [9], our SAE encodes into a sparse, higher-dimensional latent representation where , and decodes it to reconstruct by minimizing the L2 loss . We enforce sparsity on through various methods, detailed below.

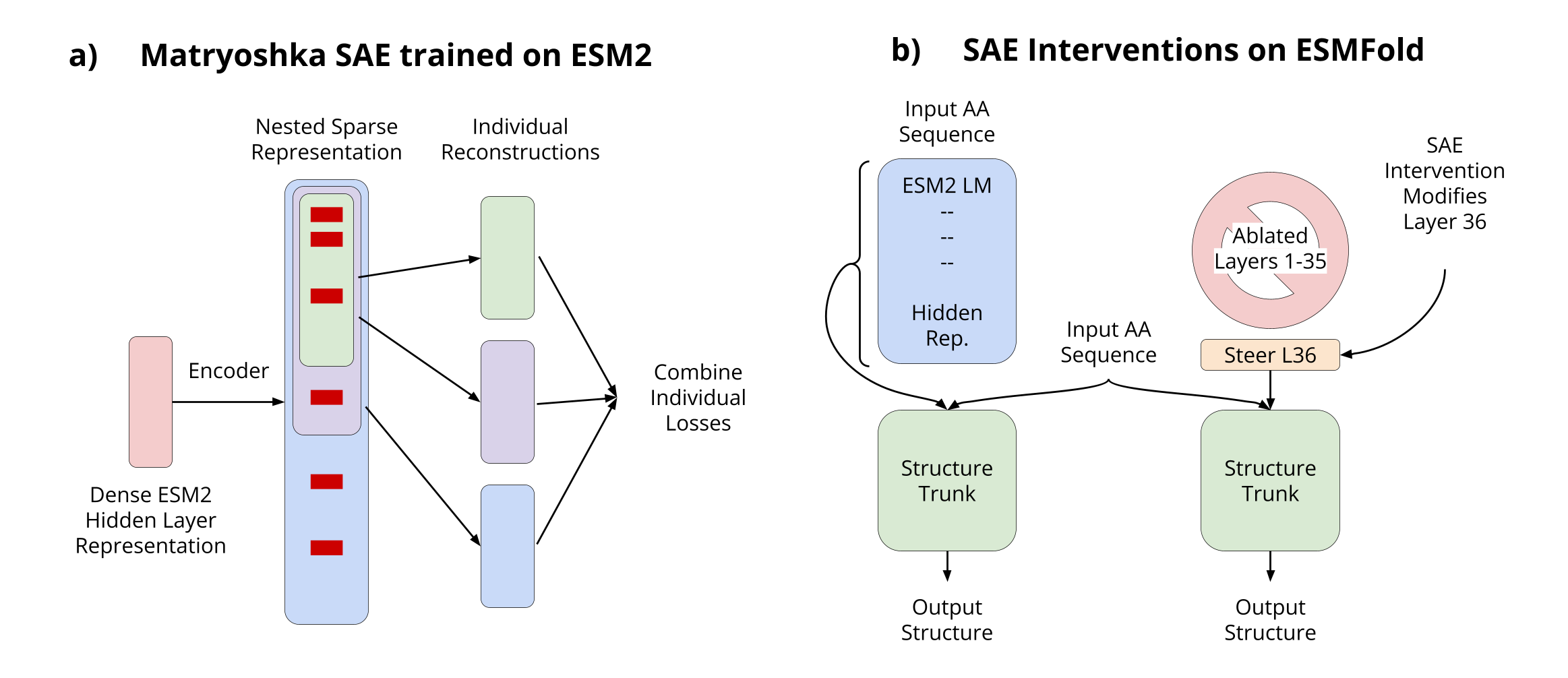

2.2 Matryoshka SAEs

Proteins exhibit inherent hierarchical organization across scales, from local amino acid patterns to molecular assemblies. To capture this multi-scale nature, we employ Matryoshka Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) [3], which learn nested hierarchical representations through embedded features of increasing dimensionality.

The key innovation of Matryoshka SAEs lies in their group-wise decoding process. We divide the latent dictionary into nested groups of increasing size, where each group must independently reconstruct the input using only its allocated subset of latents. This naturally encourages a feature hierarchy.

The encoding process follows standard SAE practices:

3. Evaluations on Downstream Loss

3.1 Language Modeling

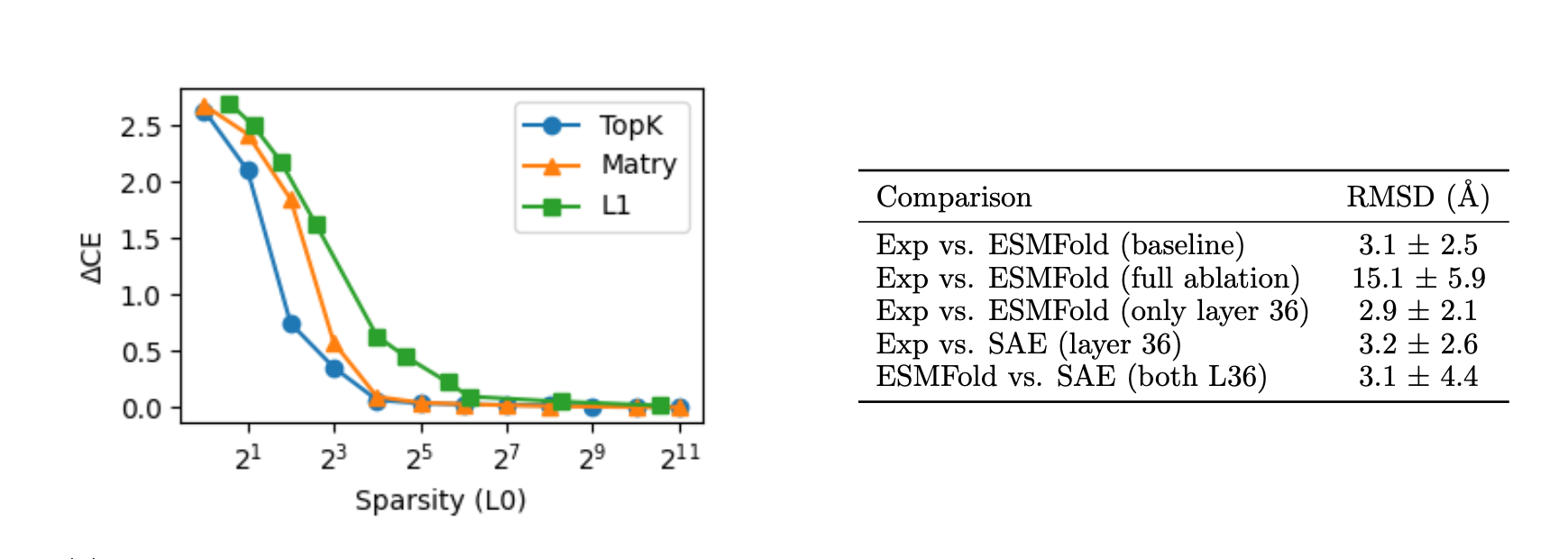

We first evaluate how well our SAE reconstructions preserve language modeling capabilities across different architectures and sparsity levels. We measure this by reporting the average difference in cross-entropy loss (ΔCE) between the original and SAE-reconstructed model predictions on a held-out test set of 10,000 sequences from UniRef50.

3.2 Structure Prediction

A key innovation in our work is extending SAE analysis to structure prediction. Since ESMFold uses representations from all ESM2 layers, we employ an ablation strategy to isolate reconstruction effects, keeping only layer 36 representations and ablating all others. Remarkably, this ablation maintains performance on the CASP14 test set.

4. Further Evaluations

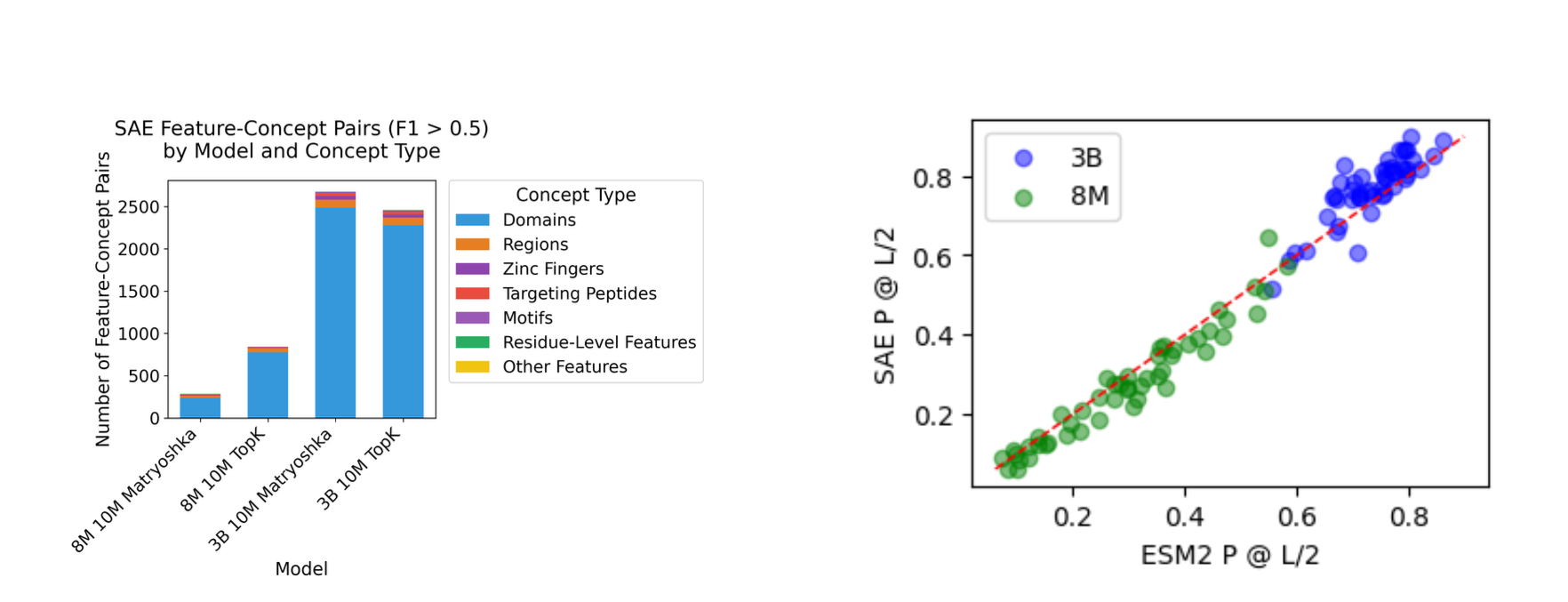

4.1 Swiss-Prot Concept Discovery

To evaluate feature interpretability, we assess how well our learned features align with biological annotations in the Swiss-Prot database. We analyze 30,871,402 amino acid tokens across 476 biological concepts, identifying features that capture concepts with F1 > 0.5 using domain-level recall with post-hoc [0,1] activation normalization.

4.2 Contact Map Prediction

Following Zhang et al. [4], we evaluate our SAEs' ability to capture coevolutionary signals through contact map prediction using the Categorical Jacobian method. This provides an unsupervised test of whether our compressed representations preserve the structural information encoded in the original model.

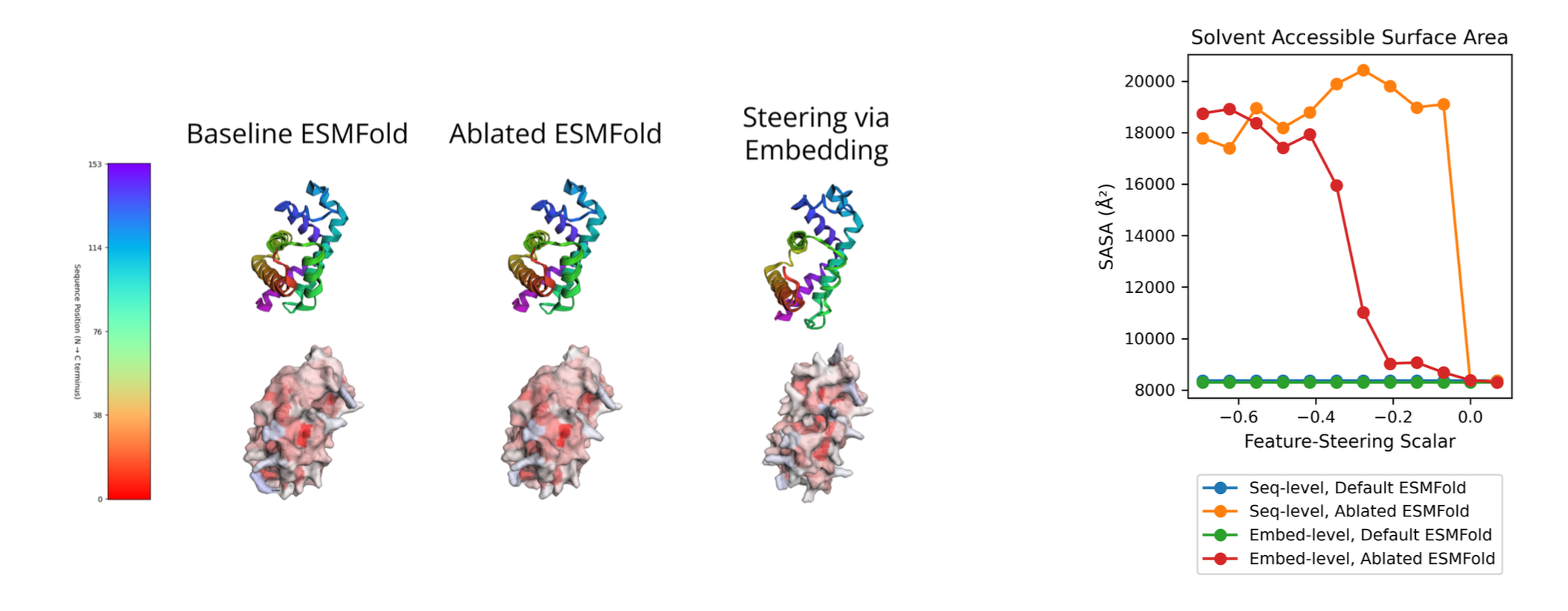

5. Case Study: SAE Feature Steering on ESMFold

To demonstrate the causal relationship between our learned features and structural properties, we present a case study on feature steering. By identifying features correlated with solvent accessibility and manipulating their activations, we show that we can control this structural property while maintaining the input sequence. We used FreeSASA [5] to compute the solvent accessible surface area for our structural models.

6. Interactive Visualizer

We've developed a web-based tool that visualizes the hierarchical features discovered by our Matryoshka SAEs. The interface displays how features from different groups activate on protein sequences, connecting sequence patterns directly to structural outcomes. Users can observe feature activations highlighted on amino acid sequences, view the corresponding 3D structure, and access AI-generated feature descriptions based on patterns observed across 50,000 SwissProt proteins. This tool not only demonstrates our approach but provides researchers an intuitive way to understand how specific sequence patterns influence structural predictions—bridging interpretability research with practical protein engineering applications.

7. Discussion

This work advances protein language model interpretability by scaling sparse autoencoders to ESM2-3B, extending recent work [6][7] using SAEs to interpret protein language models to the structure prediction task. Through a combination of increasing model scale, leveraging the Matryoshka architecture, and targeted interventions on ESMFold's structure predictions, we present the first application of mechanistic interpretability to protein structure prediction.

Key Insights

Our research yielded several important findings:

- Scale matters significantly for feature interpretability. The jump from 8M to 3B parameters led to a dramatic improvement in biological concept coverage (from ~15-20% to ~49% of concepts), particularly for protein domains.

- Hierarchical feature organization through Matryoshka SAEs provides comparable or better performance than standard architectures while offering a more structured representation aligned with the multi-scale nature of proteins.

- Structure prediction requires surprisingly few features. Our ablation studies showed that with only 8-32 active latents per token, SAEs can reasonably recover structure prediction performance, suggesting the essential structural information may be more compact than previously thought.

- Feature steering can control structural properties while maintaining sequence integrity, demonstrating a causal connection between specific features and structural outcomes.

- Coevolutionary signals are preserved in our compressed representations, supporting Zhang et al.'s [4] finding that PLMs predict structure primarily by memorizing patterns of coevolving residues.

8. Conclusion

In this work, we've demonstrated that the interpretability techniques developed for language models can be successfully scaled to state-of-the-art protein structure prediction. By training sparse autoencoders on ESM2-3B, the base model for ESMFold, and introducing the Matryoshka architecture for hierarchical feature organization, we've taken a significant step toward mechanistic interpretability of protein structure prediction.

This work opens new possibilities for understanding how protein language models translate sequence information into structural predictions, potentially enabling more principled approaches to protein design and engineering. As we continue to make these complex models more interpretable, we move closer to extracting fundamental biological insights from the patterns they've learned.

The code and trained models are available here, and the visualization tools are available at sae.reticular.ai to facilitate further investigation by the research community. We hope these resources will accelerate progress in both protein model interpretability and structure prediction.

Cite this paper

@misc{parsan2025interpretableproteinstructureprediction,

title={Towards Interpretable Protein Structure Prediction with Sparse Autoencoders},

author={Nithin Parsan and David J. Yang and John J. Yang},

year={2025},

eprint={2503.08764},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={q-bio.BM},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.08764},

}

References

- 1. Lin, Z., Akin, H., Rao, R., Hie, B., Zhu, Z., Lu, W., Smetanin, N., Verkuil, R., Kabeli, O., Shmueli, Y., Costa, A. S., Fazel-Zarandi, M., Sercu, T., Candido, S., & Rives, A. (2022). Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic level protein structure with a language model. bioRxiv.

- 2. Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., Tunyasuvunakool, K., Bates, R., Žídek, A., Potapenko, A., et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596(7873), 583-589.

- 3. Nabeshima, N. (2024). Matryoshka sparse autoencoders. AI Alignment Forum.

- 4. Zhang, Z., Wayment-Steele, H. K., Brixi, G., Wang, H., Kern, D., & Ovchinnikov, S. (2024). Protein language models learn evolutionary statistics of interacting sequence motifs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(45), e2406285121.

- 5. Mitternacht, S. (2016). FreeSASA: An open source C library for solvent accessible surface area calculations. F1000Research, 5, 189.

- 6. Simon, E., & Zou, J. (2024). InterPLM: Discovering interpretable features in protein language models via sparse autoencoders. bioRxiv.

- 7. Adams, E., Bai, L., Lee, M., Yu, Y., & AlQuraishi, M. (2025). From mechanistic interpretability to mechanistic biology: Training, evaluating, and interpreting sparse autoencoders on protein language models. bioRxiv.

- 8. Vig, J., Madani, A., Varshney, L. R., Xiong, C., Socher, R., & Rajani, N. F. (2021). BERTology meets biology: Interpreting attention in protein language models. arXiv preprint.

- 9. Rao, R., Meier, J., Sercu, T., Ovchinnikov, S., & Rives, A. (2021). Transformer protein language models are unsupervised structure learners. International Conference on Learning Representations.